A captured star has experienced multiple close encounters with a supermassive black hole in a distant galaxy — and possibly even survived having material ripped away by immense gravitational tidal forces.

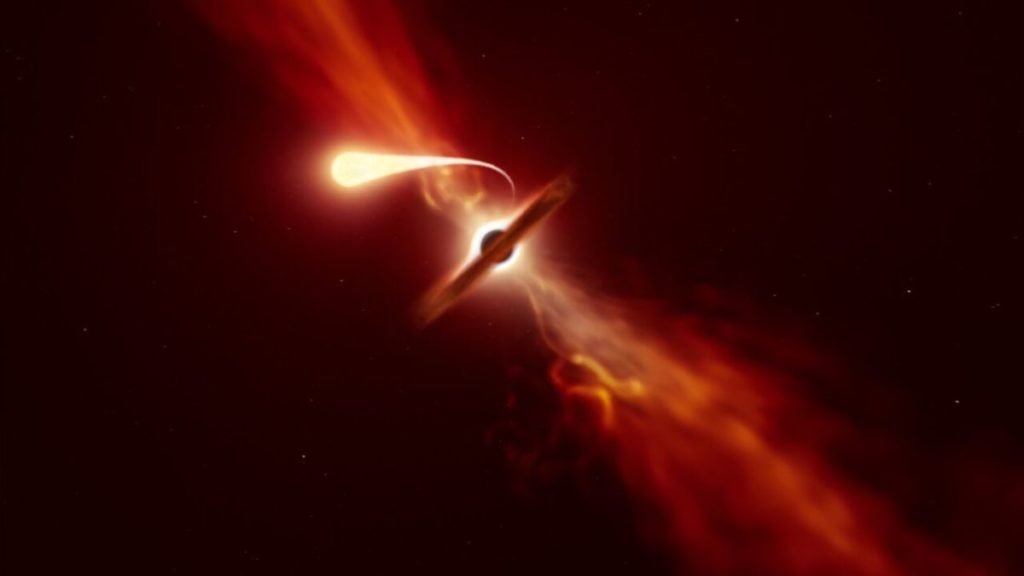

The destruction of a star by the gravitational forces of a supermassive black hole is a violent affair known as a tidal disruption event (TDE). Gas is torn from the star and undergoes “spaghettification,” in which it is shredded and stretched into streams of hot material that flow around the black holeforming a temporary and very bright accretion disk. From our point of view, the center of the galaxy housing the supermassive black hole seems to flare.

On Sept. 8, 2018, the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASASSN) spotted a flare in the nucleus of a distant galaxy 893 million light-years away. Cataloged as AT2018fyk, the flare had all the hallmarks of a TDE. Various X-ray telescopes, including NASA’s SwiftEurope’s XMM-Newtonthe NICER instrument mounted to the International Space Station, and Germany’s ROSITEobserved the black hole brightening dramatically. Ordinarily, TDEs exhibit a smooth decline in brightness over several years, but when astronomers looked again at AT2018fyk about 600 days after it had first been noticed, the X-rays had quickly vanished. Even more puzzling, about 600 days after that, the black hole suddenly flared up again. What was going on?

Related: 8 ways we know that black holes really do exist

“Until now, the assumption has been that when we see the aftermath of a close encounter between a star and a supermassive black hole, the outcome will be fatal for the star; that is, the star is completely destroyed,” Thomas Wevers, an astronomer at the European Southern Observatory and an author of new research about the event, said in a statement. “But contrary to all other TDEs we know of, when we pointed our telescopes to the same location again several years later, we found that it had re-brightened.”

Wevers led a team of astronomers who realized that the repeated flares were the signature of a star that had survived a TDE and completed another orbit to experience a second TDE. To fully explain what they were observing, Wevers’ group developed a model of a “repeating partial TDE.”

In their model, the star was once a member of a binary system that passed too close to the black hole at the center of its galaxy. The black hole’s gravity flung one of the stars away, which transformed into a runaway hypervelocity star racing at 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) per second out of the galaxy. The other star became tightly harnessed to the black hole, on a 1,200-day elliptical orbit that took it toward what scientists call the tidal radius — the distance from the black hole at which a star starts to be ripped apart by the gravitational tides emanating from the black hole.

Because the star was not fully within the tidal radius, only some of its material was stripped away, leaving a dense stellar core that continued on its orbit around the black hole. It takes approximately 600 days for the material pulled from the star by the black hole to form the accretion disk, so by the time astronomers saw the system flare, the star was safe, near the most distant point of its orbit.

But as the star’s core began to approach the black hole again, about 1,200 days after its first encounter, the star began to steal back some of its material back from the accretion disk, causing the X-ray emission to suddenly fade. “When the core returns to the black hole it essentially steals all the gas away from the black hole via gravity, and as a result there is no matter to accrete and hence the system goes dark,” Dheeraj Pasham, a co-author on the study and an astrophysicist at MIT, said in the statement.

But the black hole’s gravity soon returns the favor, stealing more material at the star’s close approach. As during the initial encounter, there’s a 600-day lag from the black hole snacking on the star to the formation of the accretion disk, explaining why the X-ray flare switched back on when it did.

From the star’s orbit, Wevers’ team calculated that the black hole has a mass nearly 80 million times that of our sun, or about 20 times more massive than the black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy, Sagittarius A*.

Wevers’ team won’t have to wait long to find out if the theory is right. The scientists predict that AT2018fyk should go dark again in August, when the core of the star comes back around, and brighten again in March 2025 when new material begins accreting onto the black hole.

However, there’s one potential complication in the amount of mass the star has lost to the black hole. The amount of lost mass depends partly on how fast the star is spinning, which the black hole might be affecting. If the star is spinning nearly fast enough to break apart, then the black hole will more easily steal material, increasing the mass loss.

“If the mass loss is only at the 1% level, then we expect the star to survive for many more encounters, whereas if it is closer to 10%, the star may have already been destroyed,” Eric Coughlin, a co-author on the study from Syracuse University in New York, said in the statement.

Regardless, TDEs and repeating partial TDEs provide a rare window into the lives of supermassive black holes that we cannot normally detect because they are dormant. This is important for measuring their mass and determining something about how the black holes have evolved, and hence how the galaxy around the black hole has also evolved over cosmic history.

The findings were presented at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society and published in The Astrophysical Journal Lettersboth on Jan. 12.

Follow Keith Cooper on Twitter @21stCenturySETI. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.