Teaching Billi her first words

For a lot of pet owners — including Kendra Baker — that process really took off with the start of COVID-19.

“I was spending a lot more time at home,” Baker said. “We had a lot more time together for me to actually kind of put the thought and the time really that it takes.”

For her first word, Baker chose something that she knew Billi would find motivating: “food.”

“Because Billy loves food more than anything in the entire world,” Baker said. “More than me.”

(This, by the way, is not recommended, since some animals will just become fixated on the buttons as a food reward system instead of a way of communicating.)

It took about three-and-a-half weeks of modeling the food button before Billi pressed it for the first time. Once she realized pressing the button scored her munchies, Billi was hooked — a little too hooked.

“She absolutely did [gain weight],” Baker said. “And then it was a very hard reality turn where, ‘Oh, wait a second — Mom’s not giving me food every time I press this button anymore. What?’”

For her second button, Baker chose another favorite Billi activity: “pets,” as in, “Pet me!” And then Baker made an unusual choice for Billi’s third button — the word that would become Billi’s trademark: “mad.”

“She picked up on that button faster than, I think, any of the other buttons that we’ve ever added,” Baker said. “I joke about this, but it was like she had always had this word in her mind, and I finally gave her an outlet for it, and she was like, ‘Let’s go.’ And she just really wanted to tell me when I was not up to par.”

With the other buttons, Baker would usually have to model them over and over in context for Billi to understand what they meant. But with “mad,” all it took was three examples.

“I modeled it once when I told her that she couldn’t have food, and then twice when I moved her off my lap,” Baker said. “And then the third time that I moved her off my lap, she marched straight over to that ‘mad’ button and slammed it. And there was a cat glare that accompanied it.”

Today, Billi has more than 60 buttons that she’s actually started combining into rudimentary sentences, like “want play” or “want food.”

But Billi’s vocabulary goes beyond her concrete desires. Take, for example, this irritated query of Baker:

Baker’s also taught Billi other abstract words and phrases, from time-related words (“soon” “later,” “now,” “then,” “before”), to commands (“help,” “look,” “come”), to emotions (“happy,” “mad,” and “I love you”).

But how do we know that Billi actually understands these abstract words? For example, in her mind, could the “I love you” button be interchangeable with “pets,” since both involve receiving physical affection?

“I don’t know,” Baker says. “It’s difficult because it is a really nebulous concept.”

Having said that, Baker says she added the “I love you” button a lot later than the “pets” button, and Billi doesn’t use them interchangeably — “pets” is much more popular.

“But [love] is an abstract concept,” Baker said. “So how much does she understand? Who knows? Like, does she just think that when she presses this button, I immediately give her affection? Potentially.”

The seeds of a research project

This is the big question when it comes to AIC: How do we know that Billi or Stella or any of the other cats and dogs we see on Instagram actually understand the words they’re using verses just pressing buttons as a way of getting some kind of response — whether it’s food or attention or pets, or just for the pleasure of producing a sound they might like?

As it happens, Billi is part of a research project that’s trying to answer exactly that question.

Leo Trottier, who spearheaded the project, which he named “They Can Talk,” poses the scientific query this way: “The big question is, are non-human animals using these sound buttons in what I consider kind of interesting ways?”

By “interesting ways,” Trottier means using the buttons in ways that go beyond the equivalent of lab mice pressing a button to get food. And he says they’ve actually started to see that.

We have seen things that I would have never expected to have seen,” Trottier said.

Trottier has a background in cognitive science, but he actually got involved with this project as an entrepreneur. Years ago, while getting his PhD, he got interested in this idea that a lot of the cognitive abilities humans have, animals have too. He ended up starting a company based on that idea, designing video games for cats and dogs to keep them stimulated while their owners were at work.

The project eventually fizzled out, but when Christina Hunger’s videos started going viral, Trottier’s interest in working with animals — and exploring their cognitive abilities — was renewed.

Trottier realized he could bring a scientific approach to what Hunger was doing, so he started FluentPet, a company that designs recordable buttons specifically for cats and dogs to communicate with.

Pretty quickly, he found that he had plenty of potential beta testers — within a year of Hunger’s first video, Facebook groups with thousands of people had formed, dedicated to training their dogs to communicate using buttons.

“I reached out to a number of them, and I said, ‘Hey, I have some experience making devices for dogs and cats, and I have a background in cognitive science. Would you like to improve on these DIY boards that you’re putting together with Velcro and plywood?’”

So Trottier started designing and testing prototypes. He made a few improvements — making the buttons smaller, so they were easier for small dogs, or the odd cat, to press; organizing the buttons in hexagonal regions instead of long lines to make it easier for animals to remember where each button lived; and grouping the buttons by word type — subjects, objects, actions, and social words.

It was all going well – and then came the doggy star who blew things up for Trottier: Bunny, a sheepadoodle who happened to have the gift of gab.

Bunny just had that special something. She got written up in the New York Times, Salon, and Buzzfeed, and within weeks had racked up millions of followers on TikTok. So Trottier reached out, and Bunny’s owner, Alexis Devine, agreed to help advertise FluentPet’s buttons.

Animal language studies and their troubled history

But Trottier — who dropped out of his PhD program, but remains a scientist at heart – wasn’t satisfied with just selling buttons. Thanks, in part, to Bunny, FluentPet had built up an online community of thousands of people, all sharing tips and tricks on the website’s forum on how to train their pets to talk. That’s when Trottier realized that he had the makings of a ready-made research project on his hands.

“Having all of these people who are very enthusiastic about this question and willing to participate — it felt like it would be some kind of misconduct on my part to not see if it was possible to bring all these people together to figure out what was going on,” Trottier said.

But to bring such a project to fruition, Trottier would need help — ideally from a scientist, unconnected to FluentPet. So he reached out to Federico Rossano, a professor of cognitive science at the University of California, San Diego to see if he was interested.

“My immediate response was skepticism,” Rossano said, “because I was familiar with the history of the animal language studies.”

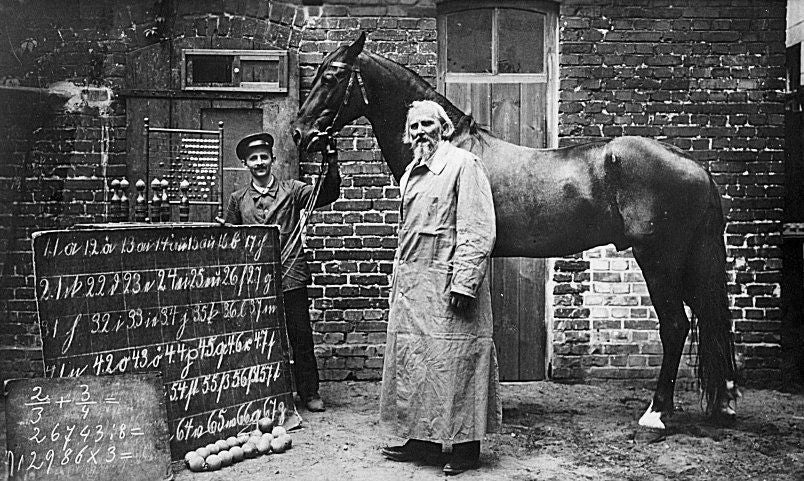

One reason for Rossano’s skepticism was what’s called the Clever Hans Effect — which is named for a horse from the early 20th century that gained fame for his ability to do math.

For example, Hans’ handler would ask him, “What’s 2 + 3?” And Hans would give the answer by stomping his hoof five times.

“And for a long time, people thought this animal was a genius,” Rossano said.

Until, that is, a psychologist came along, and showed that Hans wasn’t doing math — he was reacting to physical cues by his handler and the audience, which would relax and smile every time he got close to the right answer. Ever since then, Clever Hans has become shorthand for researchers unintentionally cueing desired behaviors in animal subjects.

But even more daunting than Clever Hans was scientists’ troubled history with animal language studies.

“They started in the 1930s,” Rossano said, “and the idea was to see whether other animals could learn language.”

Researchers began by trying to teach bonobos and orangutans to talk. When that didn’t work, they turned to sign language, and found some success — specifically with superstar primates like Koko the gorilla, who built up a vocabulary of more than 1000 signs.

At first, The project was heralded as a success — but then, in the late 70s, Rossano says, the tide turned. Critics started questioning the results, and suggesting that what we had thought was real language was, in fact, just a combination of imitation and wishful thinking.

“They were not doing anything creative or original,” Rossano said. “They were not really combining signs into meaningful sentences.”

It wasn’t language, the critics said — it was nothing more than a trick, taught through endless repetition. Worse, a lot of the animals ended up disoriented and suffering once they were placed back with other members of their own species.

“Many of these animals were highly traumatized,” Rossano said. “They showed problematic behaviors, and many of them did not live a very happy life.”

And so, this dream of teaching animals to talk died on the vine. From there, the field branched out in different directions — some researchers decided to look at how animals communicated with other members of their own species. Others stayed with human communication with animals, but looked only at comprehension (which is how we discovered that some dogs are capable of learning upwards of a thousand words). And a few others did work with using symbols to communicate.

“But again, the limitation was that usually this would be one animal, maybe two animals, that spend their entire life being trained for hours and hours and hours,” Rossano said. “And some of the findings were mostly anecdotal, right? So it was hard to conduct reliable experiments.”

So this was the backdrop swirling around in Rossano’s head when he first received Trottier’s email. His knee-jerk reaction was to decline. Science has already been over this, he thought; it’s all just wishful thinking.

Harnessing the potential of citizen science

But then Rossano started watching some of the videos Trottier had sent — specifically, of Bunny, the chatty sheepadoodle. And he couldn’t deny that what Bunny — and Christina Hunger’s dog Stella — were doing amounted to more than just a party trick.

“I was fascinated because now there’s two dogs, at least, that seem to be doing remarkable things,” he said.

Of course, as a scientist, Rossano was aware that these videos could be cherry-picked. Alone, they didn’t prove anything. What they did show was that it was possible for ordinary people to teach their dogs how to use these buttons in a fairly short period of time, and that regular dogs could build up vocabularies of dozens of words.

“What I was kind of impressed by was the idea that they were not just using one or two buttons — they had several, maybe like 20 buttons,” he said. “And so the idea was, hey, what can happen if, instead of getting just two dogs, you get 200 dogs, 2,000 dogs, 20,000 dogs, who have 40, 50 buttons?”

Rossano knew from research about human language acquisition that this threshold — 50 words — was significant. It’s when young children start producing simple, two-to-three- word sentences.

“And so the question was, is it possible that once they get to have a minimum number of buttons to use, they’re going to start combining them into sentences just like young children do by the time they are 2?” Rossano said. “And of course, the dream was, are they going to start combining more than two buttons? Maybe they’re going to make three-button combinations or four-buttons combinations.”

This was the big question that Trottier’s study might be able to answer: Are dogs and cats capable of not just memorizing words — not just using the buttons like a lever to get food or a pat on the head— but actually combining words to create sentences? To ask questions or communicate thoughts — to use language in a way that we’ve traditionally thought of as uniquely human?

These are questions that, up until now, scientists seemed unlikely to answer. Sure, we’ve seen a few superstar talking animals like Koko, or Alex the African Grey parrot. But getting to that point required thousands of hours of intensive, one-on-one work — a process that seemed neither ethical nor scalable.

But now, thanks to videos of dogs like Bunny, it was clear to Rossano that that work didn’t need to be done in a lab by specially trained researchers. It could be done in people’s homes, and it just so happened, thanks to COVID-19, there were thousands of people ready and able to do that work.

Rossano says that’s what convinced him to take part in the study — not the incredible performances of dogs like Bunny, or not only that — but the potential it held as a citizen science project. And he says the goal of the project goes beyond figuring out if animals can use language.

“Obviously they can learn it,” he said. “They can learn to associate patterns to meaning. That’s not news. What I think of this study is it’s a production study. It’s the idea that you can now see, what would they talk about if they were provided a vocabulary? What does this reveal about, for example, the way they think about humans, the way they think about other animals, the way they think about categories? Their minds and their social world and physical world?”

Early findings: Helping other pets, expressing paining, and coining new words

The first two phases of the study focus on how animals learn and use the buttons. Phase three will use behavioral experiments to test whether or not they actually understand the meaning of these words.

They haven’t yet released any findings — Rossano says their first paper should be coming out soon — so instead he talked about some of the anecdotal behaviors that have stood out to him.

One of the things Rossano’s been impressed by is seeing animals communicating on behalf of other pets in the house.

“Let’s say there’s another dog in the house or another cat and they’re stuck behind the door, or doesn’t have water or doesn’t have food,” he said. “You would find the one that can use the soundboard would go and press certain buttons to tell the human, ‘Help them.’”

Another interesting behavior that they’ve seen is animals asking for people or other pets who aren’t around — either because they’ve left the house, or, in sadder cases, passed away.

“It shows you that they have the ability to communicate about somebody that is not physically present and they think about it,” he said. “It’s not completely surprising that they can do what is called displacement, because we know that wolves know when somebody is missing and how to let them know where they are. And baboons do similar things. So many animals have ways of keeping track of who’s around them and who’s not, and call for them.”

A third thing Rossano’s found fascinating is animals communicating about their own pain, fear, or discomfort.

A particularly incredible example of this is the following video of Bunny, the sheepadoodle, who manages through her buttons to communicate what’s bothering her.

And the fourth most interesting behavior Rossano’s observed is what he calls “productivity” — combining words to create new meanings.

Take for example this dog, which saw an ambulance driving by.

“So you see them looking outside the window and coming back and looking outside the window and coming back, and then pushing the buttons ‘squeaky’ [and] ‘car,’” Rossano said. “And then they look at the human kind of like, ‘What is going on?’”

Rossano and Trottier also mentioned a few other examples. One dog, they say, started referring to ice cream trucks as “refrigerator cars.” Another, who happens to be a fan of chewing on ice, started asking for it by pressing the buttons “water” and “bone.” And Bunny, according to owner Alexis Devine, once referred to a plane as a “big upstairs bird.”

Billi, not to be outdone by her canine brethren, has coined a few of her own neologisms.

“She named one of her toys ‘catnip Bunny,’” Baker said. “It’s a beaver, but sure.”

Billi also calls her breakfast — kibble mixed with supplements and hot water — “water food.”

And maybe the most creative is what Baker says Billi named her morning coffee: “catnip water.”

Can cats and dogs assemble sentences?

So that’s all pretty interesting — but what about the goal that Rossano mentioned: finding out if, once animals had vocabularies of 50 words and up, they were able to start forming basic sentences?

He says that’s something they’ve already started seeing from their more advanced learners, like Bunny.

“One of my favorites was Bunny saying, ‘Cat dog want,’ and then repeating, ‘Cat I want,’” he said. “And so you’re like, okay — so now you have an object, the cat, that is up high. And then you’re using a noun, a subject — dog yourself; and ‘want,’ the verb. So you now have what sounds like a sentence. Is it a complete fluke, or is it actually something that you can do reliably?”

Baker says Billi is somewhat less talkative — which fits with what she’s noticed about the differences between how cats and dogs seem to use the buttons.

“One thing that I have seen between cats and dogs that is kind of like across the board is that cats really do require a bit more time than the dogs do,” Baker said, adding that Billi can take as long as 30 seconds or longer between words.

But she also says cats can be more intentional with how they speak.

“Like if they press something, they absolutely meant it,” Baker said.”Whereas dogs, it’s sometimes like, ‘Did you just run across the board? I’m not really sure exactly.’”

Billi tends to deploy sentences at strategic times — like when she’s trying to prevent Baker from leaving for work.

“There are a number of consistent ploys that she will use when that time is coming up to try and get me to stay, is what I interpret it as,” Baker said.

She recalled one morning when Billi had already exhausted several of her tactics — asking for cuddles, asking to play.

“And then I really had to go — I was going to be late — and she asked me, ‘Work where?’” Baker recalled. “And then I had to explain to her what I do for a living using her buttons. And then she pressed ‘mad.’ So I either didn’t do a very good job or she was not a fan of my answer.”

Of course, Billi and the other animals do make mistakes — there’s plenty of videos of them stringing together what seem to be random words that puzzle their owners. But Baker says, at this point, she’s fairly confident that Billi’s use of the buttons isn’t just a fluke, or some Pavlovian behavior designed to get what she wants.

“You’re never going to be able to say definitively 100%,” Baker said. “Does she probably know what some of the concrete words are? Yeah, I think we can say that with a fair amount of certainty at this point. Some of the more nebulous words, all I can really say is that she uses them in context, I would say over 80% of the time.”

So is that remaining 20% because Billi doesn’t understand? Is it the kind of normal mistakes anyone would make when they’re learning a foreign language? Or is it, as Baker suggests, for a simpler reason that any cat owner would understand?

“Sometimes she’ll press ‘catnip’ and I’ll give her some catnip and she doesn’t want it,” Baker said. “So, is that because she’s being a cat? You know, how many people have opened a door for a cat that was meowing, and then they turned around and they walked away from you. Does that mean that they didn’t want the door opened, or were they just, you know, being a cat at that point? So… it’s hard to say definitively, which is why I find the study of language in general so fascinating.”